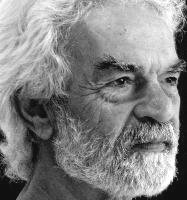

We’re sorry that Emanuel Raft is no longer with us. Raft’s contribution to Australian craft is an example of the critical contribution that migrants played, particularly to the development of contemporary jewellery. Though he positioned himself as an artist, his period as a jeweller helped establish this new art form in the heady art scene of 1960s Sydney.

Below is an excerpt from Damian Skinner and Kevin Murray. Place and Adornment: A History of Contemporary Jewellery in Australia and New Zealand. Auckland, N.Z.: Bateman, 2014.

The Egyptian Emanuel Raft migrated to Australia in 1956, where he started studying art at the Bissietta Art School in Sydney. After a year at Brera Academy, Milan, Raft returned to Australia and became involved with the Sydney visual arts scene, particularly the circle of the Nobel-prize winning novelist Patrick White. Raft became an artist who made jewellery for exhibition rather than as a private or purely economic activity, making him a unique figure in the Australasian art scene. Rather than reflect a natural organic order, Raft’s work adopts a more expressionist interest in new forms that connect with the emotions. In doing this, Raft was one of the few Australian jewellers to use opals; he preferred rough uncut opals that gave his work a fluid texture.

Raft located his jewellery within the visual arts scene, where it was considered ‘wearable sculpture’. He lived with sculptor Clement Meadmore, who said of Raft’s Brisbane show in 1962: ‘In jewellery he has found an ideal medium for three-dimensional extension of his painting while retaining his painterly qualities in their purest form. Thus he has developed his own technique in jewellery through an intuitive search for equivalents to the sensations experienced in his paintings.’ This jewellery is located entirely within a visual arts context, unrelated to its craft history over the centuries. Also in the chorus was James Gleeson, who devoted a newspaper review to Raft’s jewellery works: ‘They are vital, beautifully made, boldly asymmetrical yet exquisitely balanced, refined in details, imaginative in the use of material, enriched by various surfaces, and above all, mysterious – as mysterious as an asteroid or a talisman.’ Echoing his praise of Larsen and Lewers’s jewellery as approaching ‘fine sculpture’, Gleeson similarly described Raft’s work as ‘small sculptures’. Certainly Raft considered his work as ‘wearable sculpture’ rather than ‘personal adornment’. As Peter Pinson writes of Raft’s work, ‘The object itself was everything’. Thus he was inclined to push jewellery beyond practicality, including a ring that wrapped itself around four fingers. This modernist approach to jewellery defined itself against its use in everyday life, and sought to invent forms that transcended convention.

Raft took up a series of lecturing positions through the 1960s and 1970s and eventually produced less jewellery, holding his last jewellery exhibition at Electrum gallery in 1977. Nevertheless, his career did have an influence in the development of the Sydney scene, introducing European jewellery techniques such as cuttlebone casting. He had a particularly strong effect on Ray Norman, who saw Raft’s 1964 exhibition of cast work and was inspired to consider that jewellery could be a form of creative expression. Even though it was evaluated in terms of another medium, sculpture, Raft’s work did offer recognition of jewellery as a serious art form.