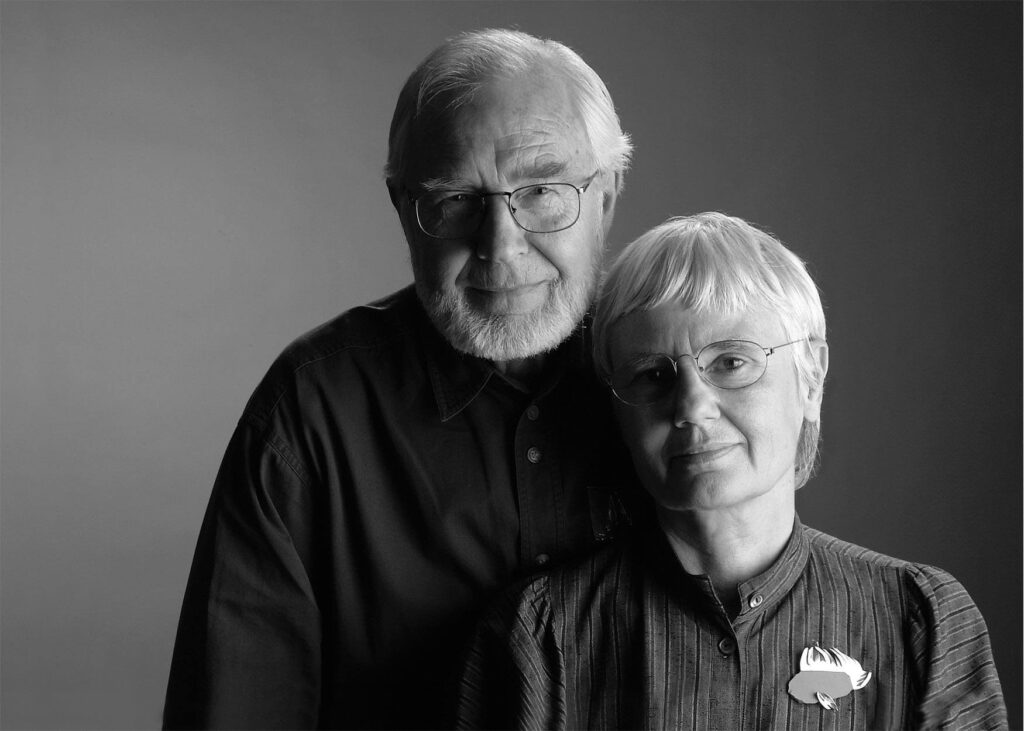

Australia mourns the loss of silversmith Helge Larsen. Australian craft owes such a huge debt to Helge Larsen. Alongside Darani, he was not only a master silversmith but a great community builder.

According to WoCCA board member Liz Williamson:

Helge Larson was an outstanding jeweller renown internationally who made a significant contribution to the Australian craft and design sector with his leadership, mentoring and advocacy. He will be remembered for his creativity and technical expertise in his practice, his generosity of spirit and willingness to share; a sincere, kind-hearted soul with a pleasant, engaging manner. Our thoughts are with his family as we send our condolences.

The following is an extract from: Skinner, Damian, and Kevin Murray. 2014. Place and Adornment: A History of Contemporary Jewellery in Australia and New Zealand. Auckland, N.Z.: Bateman.

In 1959, after training with Ots, Darani Lewers was encouraged by her father, the sculptor Gerald Lewers, to travel to Denmark . She arrived in England but found it difficult as a woman to obtain a position in the jewellery industry. After working for a while in costume jewellery, Lewers visited Copenhagen where she met Helge Larsen.

Larsen had completed an apprenticeship with Viggo Wollny, a master of the guild in Copenhagen. While he appreciated the skills he obtained there, Larsen could not relate to the ornate style that was featured in the workshop. In 1953, he had successfully undertaken the course at the Guldsmede Hojskolen (School of Art and Design). Then, in 1955, Larsen was awarded a two-year scholarship from the Danish American Foundation to study and work with the silversmith Stig Gusterman, who was producing ecclesiastical ware in Colorado. Larsen gained further experience with the University of Colorado, but of greater importance was his involvement with the Navajo jewellery scene. For a time, Larsen worked in Santa Fe, teaching jewellery skills to local Navajo people. On return to Denmark in 1957, he established his own business, Copenhagen Solvform. Larsen took Lewers on as a trainee in 1958 and 1959. Their work came to the attention of English curator Graham Hughes, who included it in the International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1890–1961 at the Goldsmiths’ Hall in London. Lewers was the only person living in Australia who featured in this exhibition, which brought together 1000 objects made during the previous 70 years, focusing particularly on artists making jewellery and on studio jewellery. Solvform broke up in 1960. In 1961 Larsen migrated to Sydney and set up a workshop with Lewers.

According to Patricia Thompson, their initial jewellery was influenced by Scandinavian craft traditions: ‘Their early work involved the simple hammered forms that originated in Scandinavia, and then they became interested in folk jewellery – “Large forms became many small forms linked together”.’ But this evolved into more geometric forms, exploring kinetic effects. The Scandinavian influence was particularly marked in Sydney in the 1960s, where Georg Jenson had opened a shop and the Swedish Baron Axel von Rappe ran Scandinavian House (1961-1967), which included jewellery and hollow-ware.

On the year of their return they had their inaugural exhibition together at Macquarie Gallery, the gallery’s first ever exhibition of this kind. The recognition of Larsen and Lewers by Goldsmiths’ Hall had secured their place in the emerging field of modern jewellery, and the exhibition was consecrated by Sun-Herald art critic James Gleeson:

The exhibition is as stimulating as a collection of fine sculpture. Indeed, many of the necklaces, pendants, rings and brooches reflect in miniature the highly wrought sophistications of the world of Arp or Brancusi . . . sensitive taste, high craftsmanship and an active imagination have been combined to make these objects into works of art.

The exhibition strengthened the aspirations of jewellery as a new form of the visual art then emerging in the Sydney scene.

While subtle, there were local references within these modernist forms. According to Judith O’Callaghan:

While rough pitted surfaces were meant to evoke the texture of the landscape, a number of pieces incorporated materials such as abalone shell and wood that Helge and Darani had collected on bush walks. Some designs were actually based on natural forms, for example, the oxidised silver pendant which suggests the shape of an explored pod, that outer shell opening to reveal a cabochon star sapphire. Local stones, such as sapphires and agates were used quite extensively but like shell and wood they were treated as a formal element complementing the metalwork, rather than as a precious point of focus.

In the early 1970s Larsen’s and Lewers’s work began to reflect more urban themes. They replaced geometric forms with designs of medieval towns, schematic urban plans and architectural features. On return to Australia, they began to focus on the local manmade environment. Their brooch, The Australian Dream, depicts the typical Australian suburban home, and they also made Harbour Bridge and Opera House pendants, engaging with national identity at a symbolic rather than a personal level. Instead of employing natural materials, they inserted photographic elements into these works.

Their approach to nature was quite experiential – as jewellers, one of Lewers and Larsen’s principal contributions was to forge an artistic attitude toward nature. Their horizon is a world based on an order flowing from, rather than imposed on, nature. In their own words:

Societies seek to order the forces of nature, while nature has its own organic structures which in turn influence societies. Our way of working involves a planned and structured approach – to create a sense of order and determine the content. We respond to and explore the imprint left by cultures on the environment as well as the order which exists in nature.

This approach represents an ongoing concern in Australian contemporary jewellery to find a language of making that enables a better understanding of the land on which European civilisation has been transplanted.